“It is earth’s most famous town, so it belongs to everybody, and to all times at once” (Christopher Morley, The Trojan horse, 1937).

The myths and epic tales of Troy, destroyed by the Greeks after a long siege more than three thousand years ago, the exploits of Achilles and Hector, the overwhelming passions, the death of young heroes have always left a deep mark on our memory and imagination.

But Troy was not only myth, it was also reality. It was not just one city, but ten cities, overlapping one on top of the other, lived between 3000 B.C. and the Byzantine period (13th century A.D.) on the same strategic site, the hill of Hissarlik in the Çanakkale region of Turkey, a short distance from the sea and overlooking the Dardanelles strait.

Until the first decades of the 19th century, Homer’s poems were considered a work of absolute fantasy, just legends told by this poetic genius of the 8th century BC, Homer.

The identification of the site of Troy and the proof that the Homeric poems were inspired by real events is due to an adventurous and imaginative German entrepreneur, Heinrich Schliemann (1822-1890), who, convinced of the historicity of the heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey, suddenly improvised himself as an ‘archaeologist’. After a difficult and needy childhood, Schliemann became rich by trading, money loan and supplying war material for the Tsar’s troops during the Crimean War. Divorced from his first wife, he married a charming young Greek woman, by whom he had two children, named Agamemnon and Andromache. His childhood dream was to find Troy, and he did really succeed, although of the many cities overlapping on the hill of Hissarlik, he mistakenly identified the city of Priam with one that was about 1000 years older (Troy II) than the real Troy of the Homeric poems (Troy VI-VII).

His figure has taken on legendary overtones because of the obstinacy with which he sought out the city on the basis of a blind and almost naive trust in the descriptions of places written in the Iliad: since the Greeks move from the siege area to the ships several times a day, the city could not have been very far from the coast; and, above all, Hector, chased by Achilles before the fatal duel that will lead to his death, runs around Priam’s fortress three times, so there could not have been any steep slopes, nor could the outer width have been too wide.

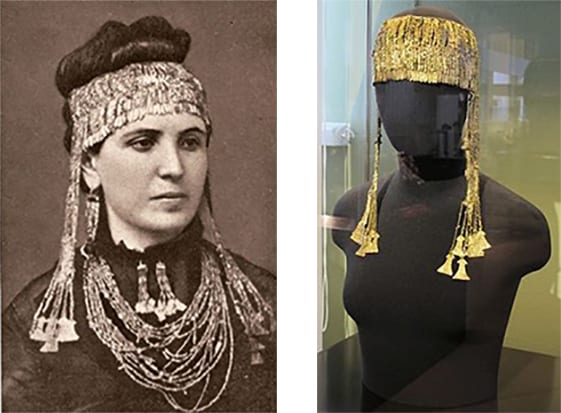

However, his hasty and invasive excavations severely damaged many archaeological layers of the city and destroyed considerable structures forever, in a spasmodic search for treasures. Moreover, in 1873 he found a deposit of precious jewellery and gold and silver pottery, the so-called ‘Priam’s treasure’, (actually from Troy II), which he brought back from Turkey without permission and, as a result, his excavation licence was revoked. Schliemann returned later part of the treasure to the Ottoman government (now in the Istanbul Museum), asking to be allowed to resume excavations; the part of the objects he kept for himself was then bought by the Imperial Museums in Berlin and displayed in the Pergamon Museum. In 1945, however, the Red Army took the finds from here and so they were sold or dispersed; today only a part of them is in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, while some others are in the Hermitage in St Petersburg.

Nevertheless, the excavations of that period at the site of Troy opened a new chapter in the protohistoric archaeology of the Mediterranean: over time the excavations have continued, offering important and unexpected data on the life of the city.

The very ancient settlements of Troy I-II-III, dated between 2920 and 2200 BC, for example, have shown unsuspected external contacts, so much so that they are collectively referred to as the ‘Trojan Maritime Culture’ due to their extensive relations with the whole of the Mediterranean, south-eastern Europe, Anatolia and central Asia.

But it is Troy VI (1740-1300 BC), surrounded by walls up to 10 metres high, that shows the greatest development. It was initially assumed that this was the Ilium narrated by Homer, but its destruction was actually caused by an earthquake. However, it was from the level of Troy VII (between 1300/1250 B.C. and 950 B.C.) that clear indications emerged of a threat and the desire to enclose oneself safely within the citadel: some of the gates in the defensive walls were walled up, warehouses for storing foodstuffs were built and the settlement became more ‘crowded’. Archaeological excavations have shown that the site was actually destroyed by a war event around 1180 BC: according to many scholars, the very war narrated in the Iliad.

Sandra Gatti