Lavinium in-depth

LAVINIUM in-depth

Lavinium – In-depth

30 Piglets

The number of 30 piglets is variously interpreted by the ancient sources. The piglets indicated the years that should pass before Ascanius founded the city of Alba Longa. The city called Alba (white) owes its name to the colour of the sow (Cato, Origines); or 30 was the number of the communities, of the populations that formed the nomen latinum and that had their common sanctuary dedicated to Jupiter on Albano Mount (Lycophron). According to Varro, the body of the sow was conserved in Lavinium in a salt solution and the bronze statue of the animal with the 30 piglets was located in the city: the image of the sow with 30 piglets is often used on the medallions of Antonine period which celebrated the foundation of Lavinium.

(from Carandini, Cappelli 2000)

turnus

The clash with Turnus, king of the near and strong city of Ardea, which Virgil put at the centre of second part of the poem, symbolises the rivalry and the historic and ancient contraposition between Lavinium and Ardea. In fact, both the cities had a sanctuary dedicated to Venus- Aphrodite (Venus was the mother of Aeneas) where took place rituals and ceremonies jointly celebrated by all the Latins. Thanks to Strabo we know that during the Augustean Age, the Aphrodision of Lavinum was managed by the Ardeans by using sacred slaves: this seems to indicate a situation of decadence and abandonment of the sanctuaries of the city of Lavinium during the late Republican Age, an hypothesis confirmed also by the archaeological data concerning the 13 altars during the same period. Therefore, It should exist a legend of Aeneas linked to city of Ardea which was a copy of the Lavinium version considering the correspondence between the monumental buildings of the two cities (also rituals was the same). An evidence of this theory is represented by the two altars found in Castrum Inui, a coastal sanctuary near Ardea. The astronomic orientation of the two altars corresponds to the description gave by Dionysus of Halicarnassus concerning the altars (bomoi) where Aeneas make sacrifices after his arrival; the minor temple of Castrum Inui could be dedicated to Aeneas (Torelli).

(Firenze, Galleria Corsini)

Mezenzio

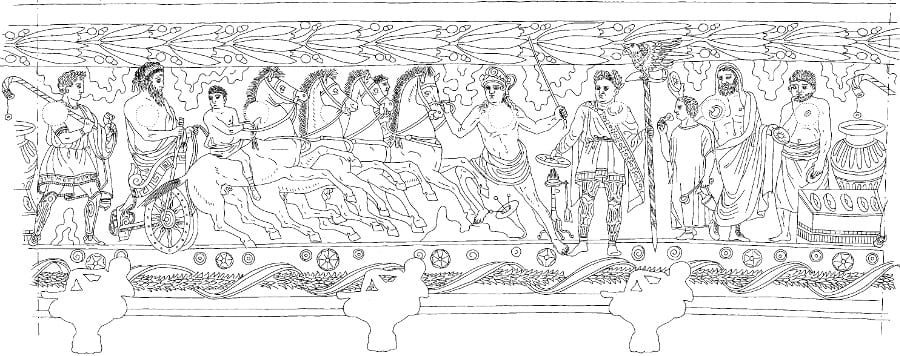

Mezenzio is an Etruscan figure mentioned by all the ancient sources, starting from Cato who narrates the latin ceremony of Vinalia priora connected to a mythic episode: the “tyrant” Mezenzio imposed to the Latins, as tribute, all the wine they produced and Aeneas managed to take the wine back. The legend, completely ignored by Virgil, was very famous indeed and It comes out very often especially in the antiquarian tradition with different variations. A rare representation of the event is possibly on a cista of Praeneste (340-330 B.C.)

(Berlin, Antikenmuseum)

(from Bordenache Battaglia 1979)

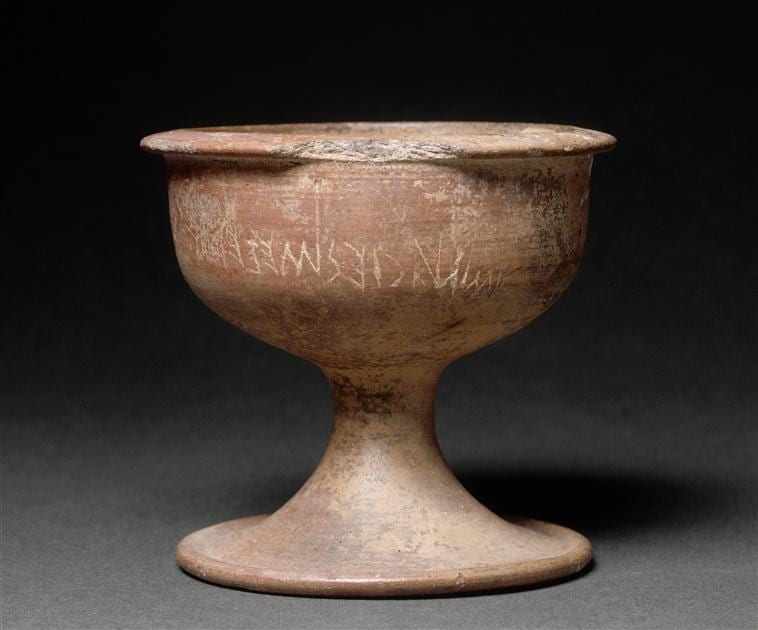

His role is variously narrated: for Cato, Mezenzio supports Turnus defeated by Aeneas; after the death of Aeneas Mezenzio is killed by Ascanius. According Dyonisus of Halicarnassus after the death of Aeneas, Mezenzio besieges the Latins but then he surrenders and becomes one of their allies. For Virgil, Mezenzio is an exiled king and Aeneas kills him and Turnus. The historicity of the figure of Mezenzio is indicated by an Etruscan inscription carved on a vase exhibited at Louvre, mi Laucies Mezenties (“I am Lucius Mezenzio”), which documents this rare noble of Italic origins. Virgil, involving the figure of Mezenzio killed by Aeneas in the Aeneid, uses an historical source.

borgo di pratica di mare

The village rises on the hill occupied in the ancient period by the acropolis of Lavinium. During the Imperial age on the same place was located a domus with black and whites mosaics. A civitas Pratica is mentioned for the first time in 1061; later sources refer to a castrum belonging to the Saint Paul Monastery until 1442. The estate of Pratica di Mare, comprehending also the borgo (village) at that time called “the castle”, became property of the Massimi family and in 1617 was acquired by the Borghese family.

(Archivio di Stato di Roma)

The Prince Giovan Battista, in his efforts to enhance the local territory with agricultural initiatives, restructured the village giving to it the current aspect we can see today with its orthogonal plan and unitarity of image. The conformation of the modern village is related to the restoration operated in the 17th century by the architect Rainaldi on the basis of the drawings of Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane. Since the second half of the 19th century the malaria, which devastated the roman countryside, caused the depopulation of the village until Camillo Borghese started the recolonisation campaign in 1880, with a huge work of reorganisation of the estate where he decided to plant vineyard with hexagonal plant. The village and the estate represent a very important monumental and rural area still intact located within the degraded area of Pomezia and Torvaianica.

Sol Indiges

The sanctuary is located on the coast, in an area which was originally a lagoon. Its most ancient period dates back to the end of VI century B.C.; at the beginning of III century B.C. the temple was built and the sanctuary was surrounded by a circuit of walls with a defensive function which involved a quadrangular area; the access to the complex was allowed by a door with two towers. This last intervention transformed the area in a sort of fortress conceived to protect the settlement by the attacks by sea. The materials found seem to indicate that the cult practices of this sanctuary was related to health and healing, maybe a temple dedicated to the god Aesculapius. The site was identified by some archaeologists as the place described by Dionysus of Halicarnassus (Ant. Rom. I, 53-56) where the ancients thought Aeneas arrived and the first Trojan encampment was settled.

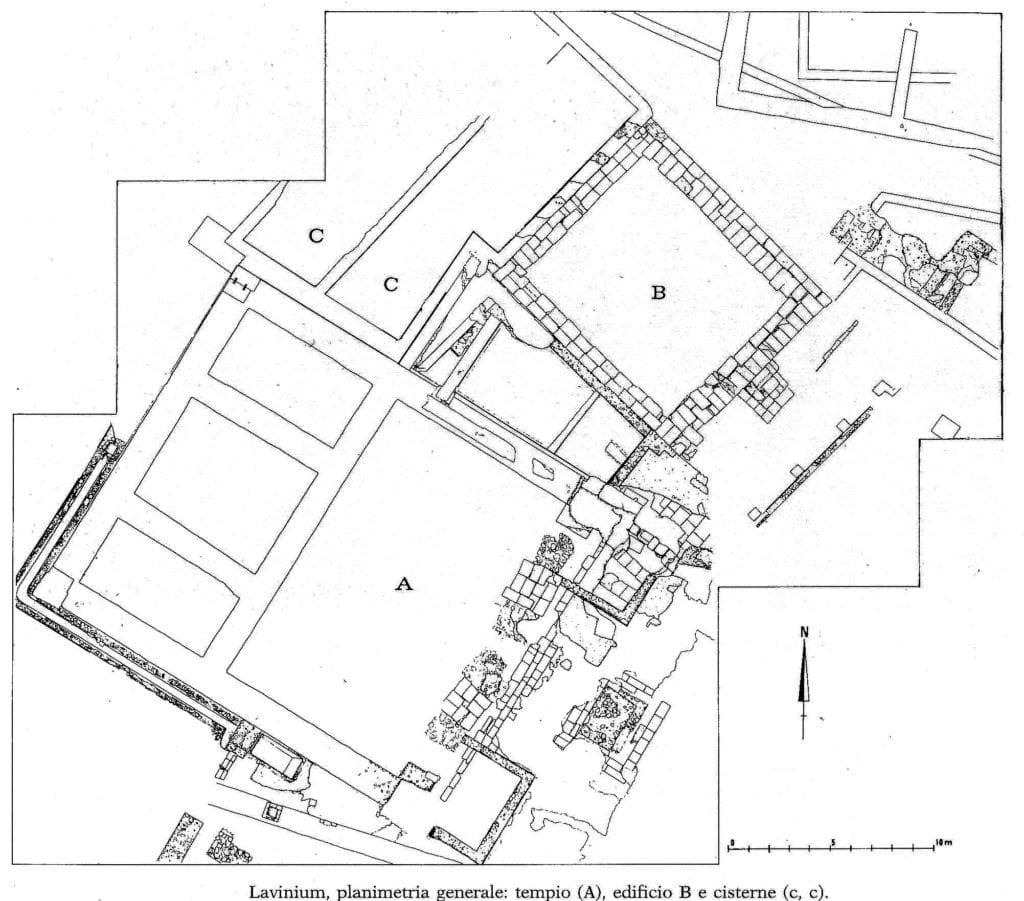

The XIII altars

The most ancient altars are built with a system called “trunk” with a perimeter of blocks of tuff filled with terrain and debris; the most recent ones consist of lined blocks. Their plan repeat the scheme of a type of altar well known in Greece, with protruding sides and a central body constituted by an original creation, with complex archaic mouldings, typical of Latium and very common until the Hellenistic period.

Common cult

The identification of the sanctuary, for which is particularly significative the boundaries with the Heroon, is controversial. Some researchers identified the area as the sanctuary dedicated to Penates but that temple would be located in center of the city; others proposed the hypothesis that the altars could be the Aphrodision of the city, the temple dedicated to Venus- Aphrodite, the mother of Aeneas, mentioned by Strabo, but probably this was located on the seaside; other scholars think that this could be the sanctuary dedicated to the Pater Indiges and the single altars was linked to the Latin colonies between VI and IV century B.C., anyway before the dissolution of the league in 338.

alba longa

According to the tradition Ascanius Iulius, son of Aeneas, founded Alba Longa, a city located on the Alba, giving rise to the lineage that will fill the years that separate the war of Troy and the journey of Aeneas (VIII century B.C.) from the foundation of Rome (VIII B.C.), by Romolus and Remus. The twins were grandchildren of the kings of Alba Longa; their mother, Rea Silva and the father the god Mars. Romolus killed Remus and founded Rome (753 B.C. according to the chronology given by Varro). Lavinium became the sacred city of the Romans, where the principles of the Roman population were based.

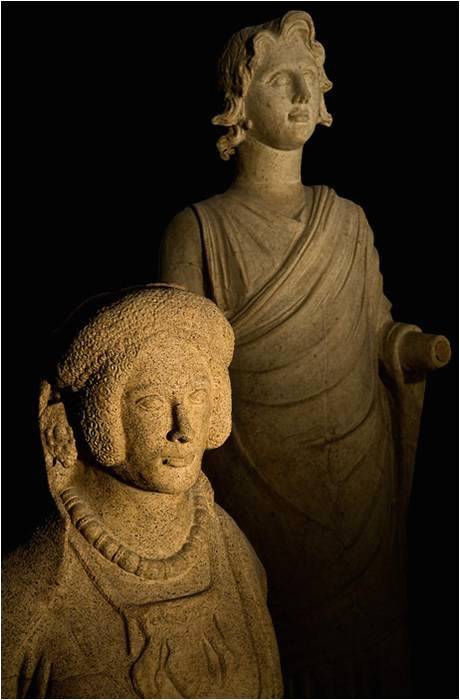

Sanctuary of Minerva

The sanctuary, situated on the east part of the ancient city, was dedicated to Minerva, who at Lavinium was a warrior goddess but also protector of the births and marriages. A deposit of votive material dated back to archaic age and early III century B.C. has been found in this area: numerous terracotta figurines representing male and female, often life-sized, with rabbits, eggs, pomegranates, toys, doves and other offers to the gods. These offers represent the passage to the adulthood with a particular reference to the marriage.

Terracotta statues of the devotes of the sanctuary of Minerva

Burial chamber

The burial chamber is a tomb bordered by walls in opus quadratum and originally covered with a false vault, consisting of protruding blocks. The construction technic used for this tomb represents an unicum. However is possible to compare the structure with some hypogeous from Tusculum of a later period. Two vases belonging to the funerary equipment were located over the most ancient urn, dated back to 570 B.C.: a Tyrrhenian amphora (of Greek production, decorated with black figures over superimposed registers) and a bigger amphora in bucchero with an inscription in Etruscan language: mini m[ulu]vanice mamar.ce : a.puniie: I am a gift from Mamarce Apunie. The peculiarity of this document is the fact that the inscription is the same found in a second dedicated vase in the sanctuary of Apollon in Veio: this indicates probably friendly relationships with exchange of gifts between families of Lavinium and the family of Mamarce Apunie and so deep boundaries between the Latin city and Veio.

Inscription of Mamarce Apunie on vases in bucchero from Lavinum (left) and from Veio (right) (detail; from Michetti 2010)

The Forum

The forensic area had a complex series of occupational phases: the most ancient is represented by tombs dated back to the Bronze Age; later in VIII and VII century .C., this area is occupied by huge houses. Subsequently the public square of the city develops a rectangular plan surrounded by several buildings. On the short side oriented to west is situated a huge temple raised on a podium of uncertain construction, maybe with three cells or with a single cell with two open wings; a stair in the frontal part and an altar in front of it; near to the temple, we could find another building- considered as the Curia of the city (a place where the local government gathered)- with rectangular plan, where the base dated back to III century B.C. and made of tuff blocks is still conserved.

Previous

Next